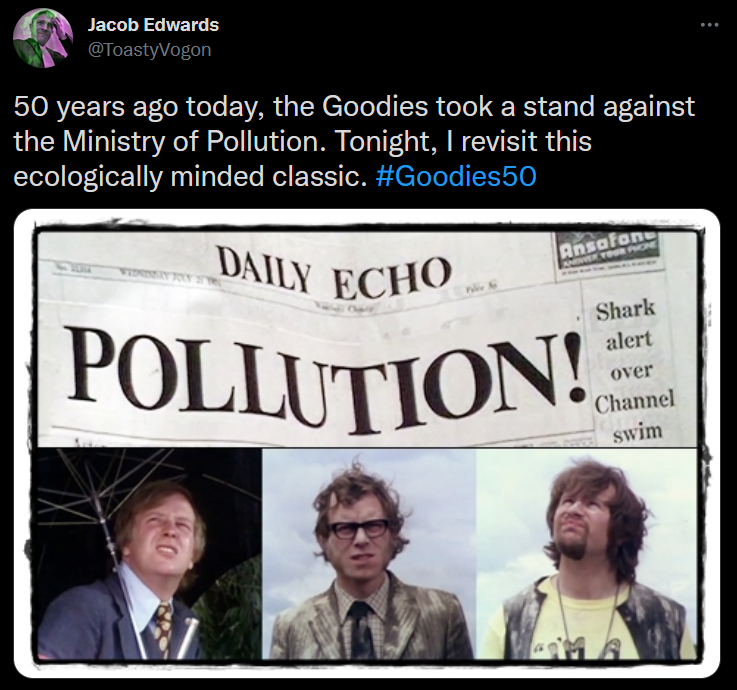

Pollution

15 October 1971

If the first two episodes of Series Two showed unrealised promise, the third reveals a new assuredness of footing. ‘Pollution’ is the Goodies’ second true masterpiece (behind ‘Radio Goodies’). It tackles its titular premise with grim wit and a sombre relentlessness that, if not accompanied by the lads’ trademark gags, would have made it a bitter pill to swallow. Instead, this mood-heavy excoriation serves as genuine satire: a warning not to be ignored. Along with ‘Culture for the Masses’ it proves the standout of 1971.

The 1970s saw environmental issues enter the public consciousness as never before. The Goodies had their say early, and, foresight aside, what sets their treatment apart even from other socially minded episodes such as ‘Hospital for Hire’ or ‘South Africa’ is the tonal seriousness they maintain while still delivering the expected comedy. One way they achieve this is via the show’s music. There is no ‘Needed’ this episode, only the mournful folk dirge ‘Changed’, a piece that balances bucolic, hopeful tones with a vivid, at times urgent sense of loss. It provides the perfect audial backdrop to the smog-filled, acid-rain-denuded dystopia that London has become under the auspices of the Ministry of Pollution.

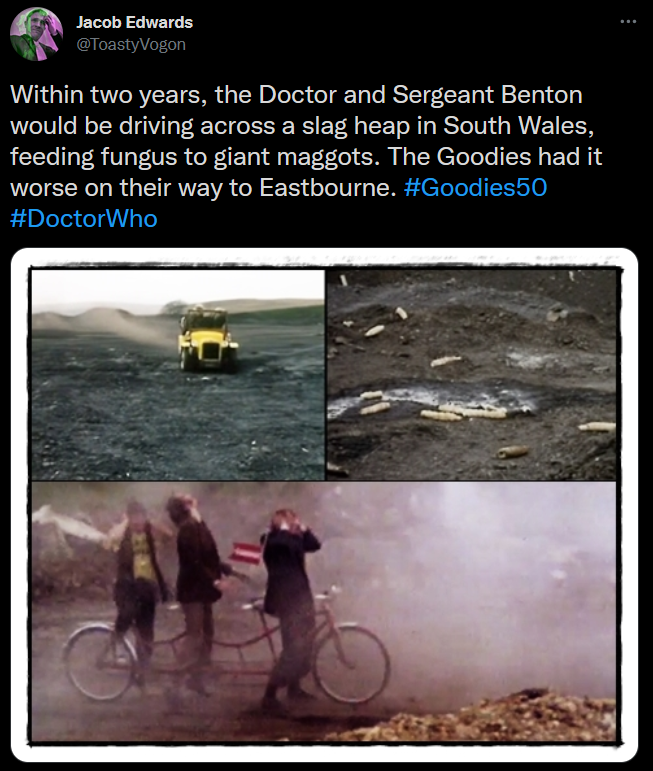

The other respect paid by the Goodies to the gravity of their subject matter comes by way of an absence. Across this episode’s 30-minute span there is no over-cranked footage and, apart from one trandem mishap towards the end and a scene where the Prime Minister clobbers Bill with a mallet, there is no falling down. In a programme where physical comedy was ubiquitous, this is no small concession. The Goodies, as mentioned previously, made a habit of winding themselves up and going beresk. They fell down a lot. They fell with the same gratuitous exuberance the Blues Brothers 2000 showed in crashing more police cars than its precursor. They fell as if for their country, for charity, as if their lives depended on it.

But not in ‘Pollution’.

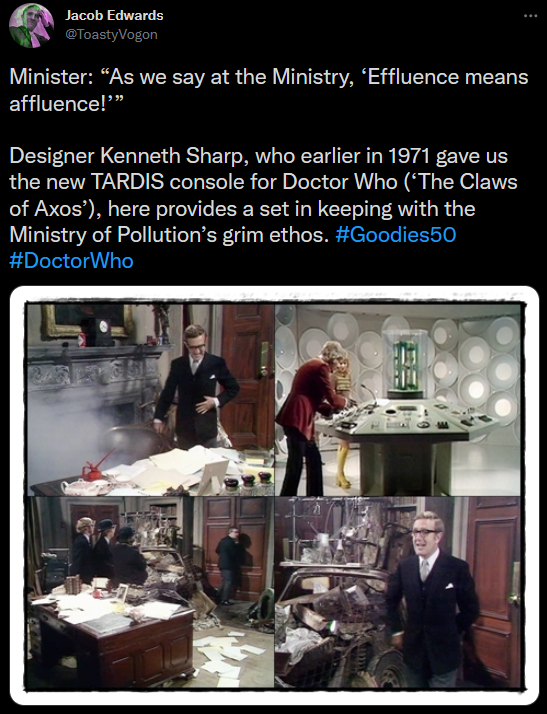

Which isn’t to suggest the episode lacks humour. The lads in fact go about their business with considerable aplomb, breaking out just about every other comedic device in their by-now-extensive repertoire. There are the customary signs (MINISTRY OF POLLUTION – CONSERVATIONISTS GO AWAY), the combined sound/sight gag of the ministerial clothes pegs (“Ah, now you sound like civil servants!”), the prop-based humour of Graeme’s extendable false arm (funny in its own right but truly sumptuous when brought back for the final handshake), and of course the tomfoolery of the lads changing places on the airborne trandem (unaccountably still pedalled as a means of propulsion!). Little acting nuances flourish throughout. BBC newsreader Corbet Woodall returns as himself (coughing repeatedly at the pollution wafting past his news desk). Ronnie Stevens hits all the right notes as the ebullient Minister of Pollution wholeheartedly embracing an insane, self-serving government policy. And, visually, the grass that swallows up London gives tremendous scope for visual humour.

The Goodies go to town, yet for the most part they wield the weapons of their craft not only to entertain but also to underscore non-humorous points. Yes, the falling of dead birds from the sky escalates to a dead sheep, but the upshot of this ‘out of nowhere’ gag is to show the situation as being even more serious than it first appears. Tim’s phone conversation with the Prime Minister likewise gives us the sped-up chipmunk squeak of information being rapidly imparted (as it would need to be to make most phone scenes work in film and television), the implied name-calling (Tim: “Well, I’ve never been called that before… Yes, I know you’ve been called that before.” ), and finally the exploding phone as a visual gag based on the PM’s rising anger. In the end, though, the point remains stark: with the world on the verge of becoming uninhabitable due to rampantly monetised pollution, the Prime Minister is still not going to address the problem.

And how do we know how bad the pollution is? Through cricket gags:

Such flippancy, of course, belies the extremity of the crisis at hand. Acid rain shreds Tim’s umbrella. Polly parrot turns canary-in-a-coal-mine and dies at the merest whiff of outside air. When Bill tempts a large Dalmatian with a dip in the toxic waste–dump sea, the result is one rapidly sinking dead dog. This is an episode oppressive in its implications. Beyond any poking of fun, or humour through exaggeration, there’s something at once chilling, prescient and very, very depressing in this underlying conceit: the government of the day, rather than acting responsibly, sets up one of its faceless, never-to-be-held-accountable ministries with the specific intention of worsening the problem and, in doing so, profiting from it. Such profiteering is both grandiose (“We shall get a 24-hour working day, 365 days a year!”) and cruelly small-scale (dudding marrow farmers), which seems especially on-point.

And who is left to save the day? The Super Chaps Three and their 20 gallons of aftershave!

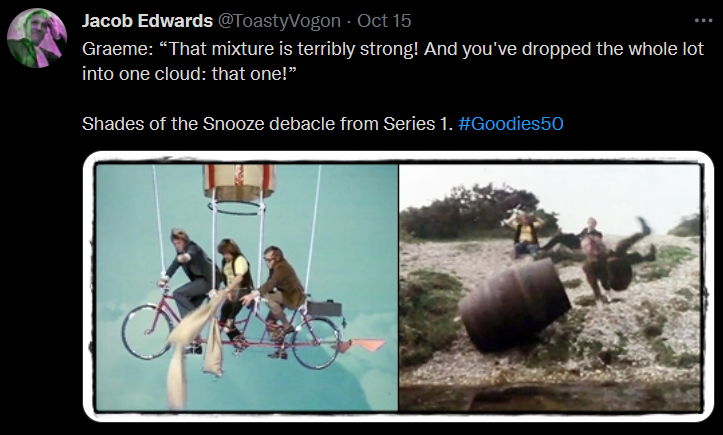

The handling, as ever, has an absurdist twist: when the minister shoots them down, the Goodies are forced to abandon their excess flight weight (the special seeding mixture; though in Graeme’s mind, Bill!). Consequently they over-seed one tiny cloud and, through dint of unfavourable winds (nicely played), thus bring about a ‘disastrous’ grassification of Central London, this newfound paradise in turn forcing us to rethink our values. Notably, this is one job in the Goodies’ early career that they undertake entirely on their own initiative. Nobody hires, tricks or coerces them. They simply do what we all should be doing.

And the ultimate message? The poison to follow the sting in the tail? No sooner have the Goodies won than the minister drops around to gleefully disabuse them. The government has nationalised lawnmowers (instant mega profit) and seizes upon the opportunity provided by all this new green space… by situating London’s new airport in the middle of the West End!

When it comes to environmental battles, each victory comes with a setback.

Jacob Edwards, 15 October 2021

Tweets:

Previous: Commonwealth Games

Next: The Lost Tribe